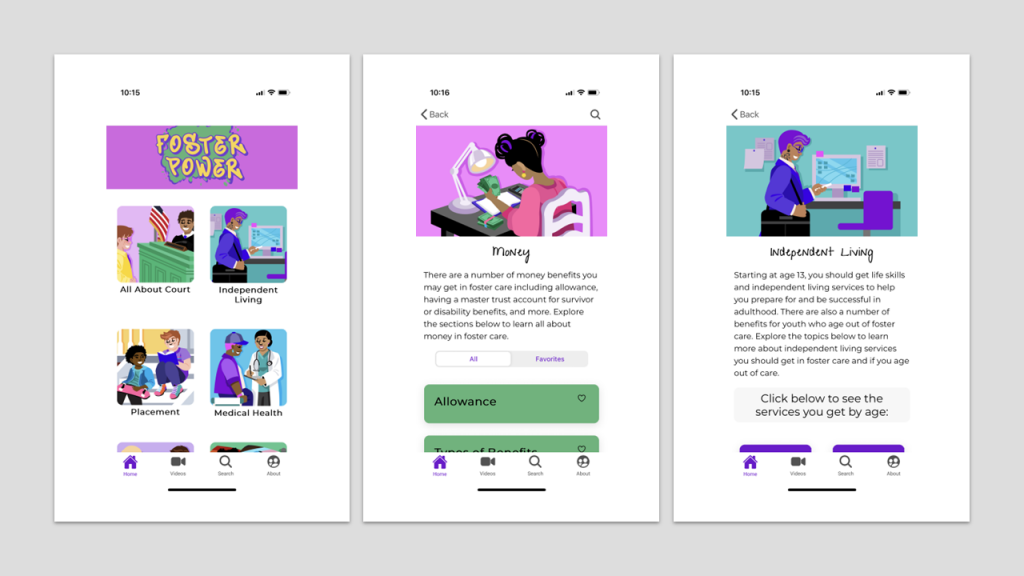

A new first-of-its-kind app and companion website, called FosterPower, provide foster youth with comprehensive but easy-to-understand information about their rights to mental health care, education and legal protections.

Developed by Bay Area Legal Services, a nonprofit law firm in Tampa, Fla., with funding from a 2021 Legal Services Corporation Technology Initiative Grant, FosterPower is designed to empower the more than 20,000 children in Florida’s child welfare system with information about their rights.

However, Taylor Sartor, the attorney who spearheaded development of the resource, said she hopes eventually to expand FosterPower into other states, most likely through partnerships with other legal aid organizations.

FosterPower provides foster youth with information on their rights in seven areas:

- Independent living.

- Placement.

- Medical health.

- Mental health.

- LGBTQ+.

- Money.

- Education.

It also includes an explanation of the court system as it applies to foster youth.

In addition to articles on these topics, FosterPower offers a variety of about 40 TikTok-style videos, most of which feature former foster youth sharing advice and experiences.

“The purpose of these videos is for kids who may not just want to read a bunch of content, to also be able to see other people’s experiences, connect with someone, and also get information from a source that they’re more likely to trust,” Sartor said.

For Sartor, the seeds for developing this app were sown when she was in law school, where she volunteered as a guardian ad litem for foster youth. As she began to research their legal rights, she discovered that Florida had no know-your-rights guide for foster care.

Even as she looked to other states, she found a few sources, but they were either far too simplistic to be helpful or far too complicated to be comprehensible for youth in foster care.

So she decided to develop a guide herself, enlisting the help of other law students and creating a 66-page booklet that was the first comprehensive guide in Florida to explain to foster youth their legal rights.

But there was a problem with the booklet, she realized. Kids lose things, and foster youth, who may move frequently, are even more prone to lose things. She kept hearing from youth that it would be better for them if the guide was online.

By then, she was working at Bay Area Legal Services as a lawyer in is L. David Shear Children’s Law Center representing foster youth, so she applied for the TIG grant to develop the app and website.

Beyond the technical development, a key goal for Sartor was to create a guide with content that struck the right balance between simplistic and complicated. It took years to get the language right, she said. In addition to her own editing, she has former foster youth review the content and has even brought in an expert in plain-language drafting.

Both the app and website contain the same content. Sartor developed both because not all youth in foster care have phones, but they generally have some way of accessing a computer. Once the app is downloaded, it is fully available offline, so youth can access the information even when they do not have Wi-Fi.

She continues to get help from law students and pro bono attorneys in keeping the content current and adding new content. She edits it all and checks all the citations and references.

This is the first app anywhere in the United States designed to inform foster youth of their rights, and Sartor’s long-term vision is to bring it to other states. That will require revising the content to conform to other states’ laws on foster care, so she hopes to partner with legal aid organizations to bring that about.

In the meantime, Sartor is focused on spreading the word about the app within Florida. She is speaking and providing training to youth advocacy organizations throughout the state and plans to continue doing that throughout the summer.

She is also continuing to collect feedback from the youth for whom the app was designed. Every part of the app, from its name down to its color palette, was decided with input from foster youth, she said, and she wants to continue to refine the app based on their input.

“We can create what we think is the best resource in the world, but if the kids don’t want it, if they don’t like it, then what’s the point.”

The FosterPower app is available on both the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.