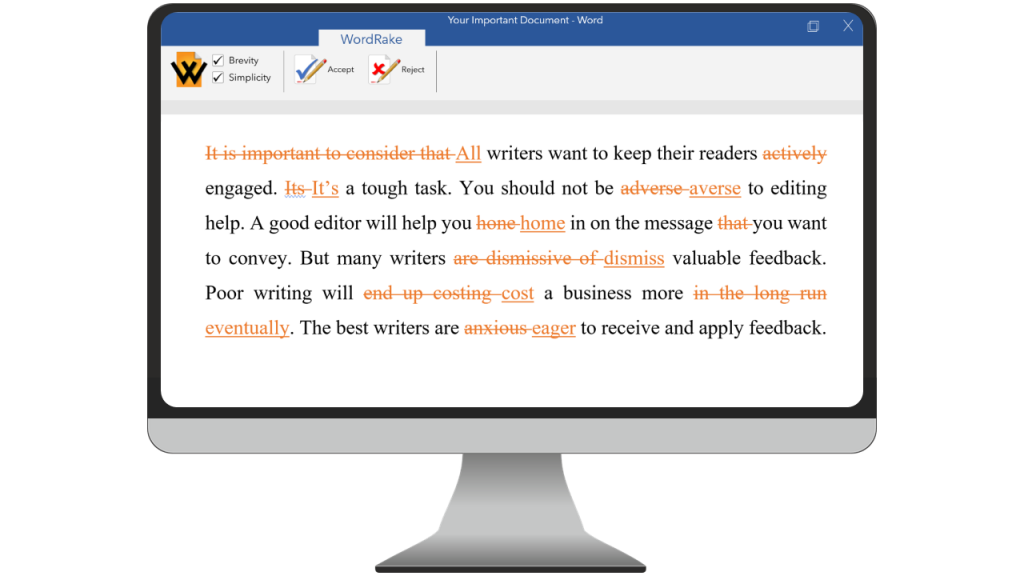

As reported here yesterday, the legal editing software WordRake released a new version 4.0 that expands its functionality, adds new pricing options for less-frequent users, and introduces a new Simplicity editing mode for simplifying complex language.

With this release, WordRake now has two editing modes: Brevity and Simplicity. You might consider the Brevity mode to be “classic” WordRake, in that it does what WordRake has always done — suggest edits that can make a document more concise.

The new Simplicity mode focuses on making suggestions designed to simplify complex language. It converts jargon, bureaucratic language and difficult words into words that are more familiar, WordRake says.

Read about WordRake in the LawNext Legal Technology Directory.

In previous blog posts, I have tested WordRake by using it to evaluate suggested edits to Supreme Court opinions. To read those previous reviews, see:

- We Test WordRake’s Beta Version 2.0 on ‘McCutcheon’.

- The WordRake Editing Program Takes on Scalia, Kagan and El Pollo Loco.

- Putting Justice Gorsuch to the Test of Three Legal Editing Programs.

WordRake gave me a preview copy of this new version 4.0, so, in keeping with those prior posts, I decided to do the same.

Having recently used a different legal editing software, BriefCatch, on the leaked draft of Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion overturning Roe v. Wade (I Ran Justice Alito’s Draft Abortion Opinion through the BriefCatch Legal Editing Software. Here’s What Happened), I chose another controversial opinion from the court’s most-recent term, the Second Amendment case of New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, written by Justice Clarence Thomas.

‘Raking’ the Opinion

I downloaded the PDF and converted it to Word, selected WordRake’s new Simplicity mode, and hit the Rake button. It took roughly 10 minutes for WordRake to analyze the lengthy opinion (132 pages in Word, including dissents). When it was done, it told me that it had analyzed 2,585 sentences and made 232 suggestions.

In fairness, a Supreme Court opinion may not be the best document for testing the Simplicity mode, as it has most certainly been through multiple rounds of editing and editors before it is released to the public. On the other hand, if an editing program can find ways to clean up a document such as a Supreme Court opinion, imagine what it can do for your brief.

What Simplicity mode found were a number of repetitive and relativity minor editing suggestions. They included, for example:

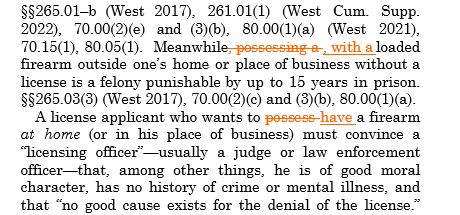

- Change “possess” to “have”

- Change “nevertheless” to “still.” (Notably, when nevertheless appeared in a quoted phrase, WordRake did not suggest changing it.)

- Change “demonstrates” to “shows” (or “demonstrate” to “show”)

- Change “allows him to carry” to “lets him carry”

- Change “does not suffice” to “is not enough”

- Change “has not demonstrated” to “has not shown”

- Change “precludes” to “prevents”

- Change “reiterated” to “repeated” (or “reiterate” to “repeat”)

- Change “prior decision” to “past decision”

- Change “initial conclusion” to “first conclusion”

- Change “attempted to” to “tried to”

- Change “for instance” to “for example”

- Change “therefore” to “so”

- Change “confine” to “limit”

- Change “appears to” to “seems to”

- Change “permitted” to “allowed”

- Change “employ” to “use”

- Change “provided” to “stated”

As you can see, none of the suggestions are particularly substantive, but that may be the point, and it certainly may be due to the nature of the document I analyzed.

As I have previously noted in writing about this and other legal editing programs, users should never blindly accept an editing program’s suggestions, as they are sometimes wrong. In the snippet above, for example, the suggested change of “possessing a” to “with a,” results in a sentence that makes no sense.

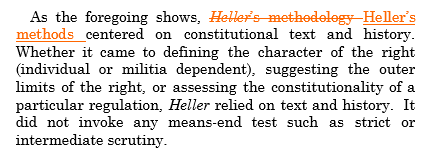

Similarly in this example, the change of “methodology” to “methods” changes the meaning to something the author did not intend.

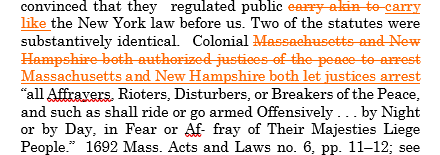

Here is one more example, where WordRake suggests changing the phrase “justices of the peace” to just the single word “justices.” The problem, of course, is that these are terms of art that have different meanings.

I also ran the document through the original Brevity mode. This time, it took 11 minutes, and from the 2,585 sentences it analyzed, it made 499 suggestions.

Many of the suggestions in Brevity mode were the same as those in Simplicity mode, such as changing “nevertheless” to “still” and the like. A number of other suggestions were to eliminate transitional words and phrases such as “moreover” or “in other words.” In other places, it suggested a different transition, such as changing “that said” to “however.”

Here again, WordRake made some erroneous suggestions. For one, it recommended changing the phrase, “the courts generally proceed to step two,” to, “the courts generally step two.”

If I accepted all of the suggestions in Brevity mode (without regard to whether I should accept them), it reduced the word count from 42,448 words to 41,564, or 884 words.

Bottom Line

The use of any editing software should be guided by your own editorial judgment. Just because a program says you should do something, that doesn’t always mean you should.

That said, my experiences using WordRake suggest that it can be a useful product for honing and editing one’s writing. Not only does it provide an extra level of review for your writing, but it can also show you how you can make your writing more concise and direct. Given its affordable cost, and especially with its new monthly pricing, it is worth adding to your toolkit.